China's New Export Control Regulations: Products Containing Chinese Materials or Using Chinese-Origin Technology Can Be Subject to Control

China‘s version of FDP rule

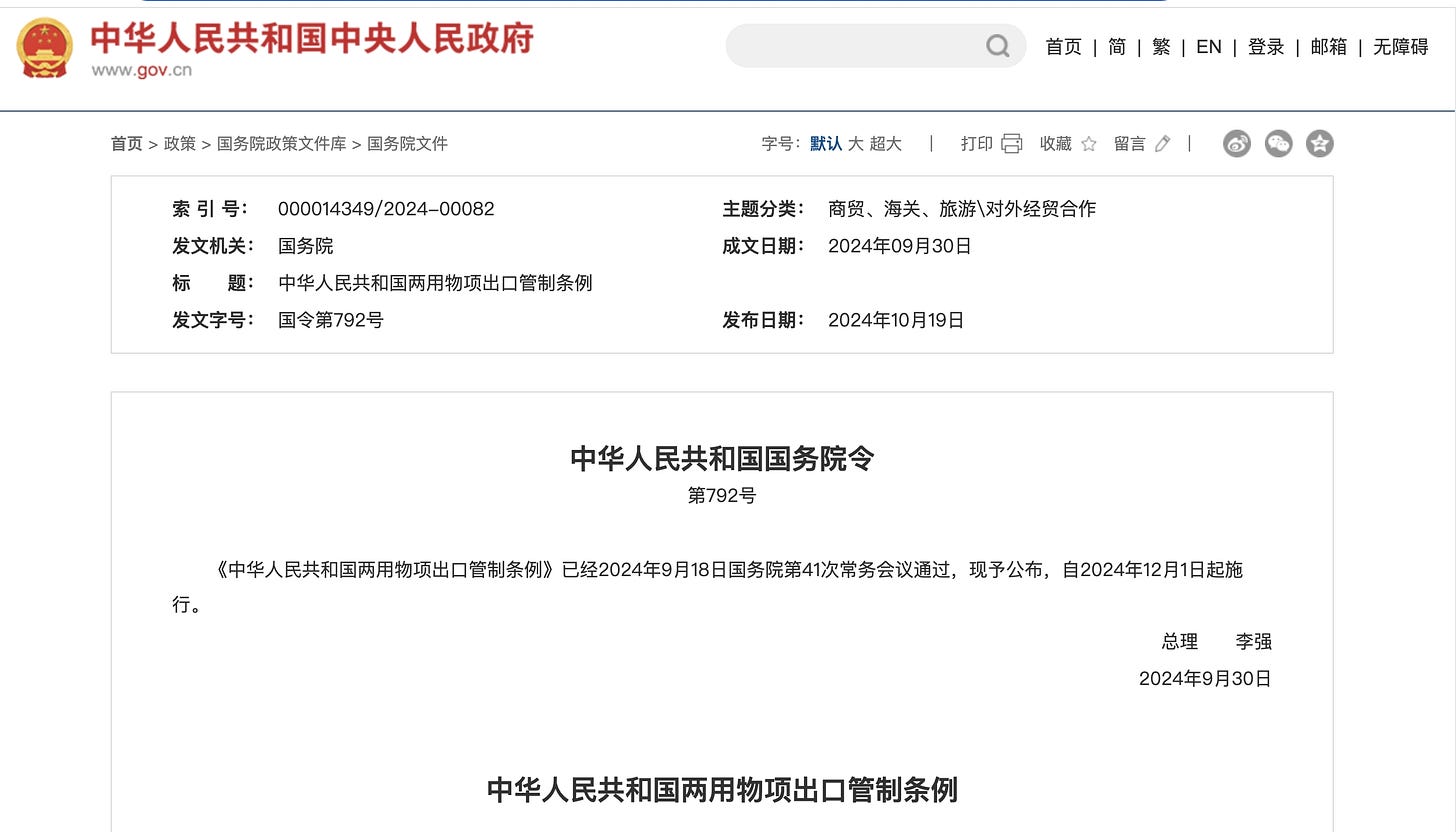

On October 19, after extensive internal research, public consultation, and field visits to companies, as well as expert roundtables, China finally issued its "Export Control Regulations."

China's modern export control system began in the 1990s. In 1992, China joined the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Two years later, the first export control rule, the "Nuclear Export Control Regulations", was released. During this period, China’s export control mainly focused on fulfilling its non-proliferation obligations and preventing the spread of weapons of mass destruction, though national security was also a policy goal, albeit secondary.

Article 1 of the "Nuclear Export Control Regulations":

In order to strengthen control over nuclear exports, prevent unauthorized acts by the State Council, safeguard national security and public interests, and promote international cooperation for the peaceful use of nuclear energy, these regulations are hereby formulated.

The year 2020 marked a significant turning point for China's export control system. China introduced its first comprehensive Export Control Law, which unified the previously fragmented export control rules. In this key piece of legislation, "maintaining national security" was elevated to the highest priority, while the previously emphasized goal of "fulfilling non-proliferation obligations" was made secondary.

Article 1 of the “Export Control Law”:

This Law is enacted to safeguard national security and interests, fulfill non-proliferation and other international obligations, strengthen and regulate export controls.

Since then, China’s export controls, along with tools like the “Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law” and the “Unreliable Entity List Regulations”, have been used more frequently as countermeasures against U.S. sanctions.

In July 2023, China's Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) announced export controls on gallium and germanium. According to the South China Morning Post, the U.S. has only 4,500 tons of gallium, accounting for less than 1.6% of global reserves, and relies entirely on imports. Between 2018 and 2021, 53% of the U.S.’s gallium came from China. Major global importers of germanium include the EU (14,068,700 kg), the U.S. (3,374,610 kg), Japan (6,382,430 kg), and Germany (5,097,240 kg), with China being the largest exporter, supplying 21,914,100 kg.

In August 2023, MOFCOM announced export controls on certain drone engines, key payloads, radio communication equipment, and civilian anti-drone systems. It also implemented a temporary two-year export control on some consumer-grade drones and prohibited the export of all civilian drones for military purposes. According to Chinese customs data, the total export value of China’s drone-related products in 2022 was 7.169 billion RMB, with about 2.32 billion RMB exported to the United States, accounting for over one-third of the total. Of the eight categories of drones regulated by the Ministry of Commerce, China exported a total of 1,004,894 units in 2022, with 420,021 units sold to the U.S., making up over 40%. The Five Eyes countries, along with Japan and South Korea, bought a total of 749,919 units, accounting for over three-quarters of the exports.

In October 2023, MOFCOM announced export controls on graphite. According to Chinese customs data, in the first nine months of 2023, China’s artificial graphite exports increased by 45% year-on-year, reaching 424,706 metric tons. The largest buyers of Chinese graphite include Japan, the U.S., India, and South Korea. The U.S. has not yet engaged in domestic graphite mining. In 2021, the U.S. relied entirely on foreign sources for its 53,000 tons of graphite usage, with China being the largest supplier, accounting for one-third of the total.

The "Export Control Regulations" issued today are somewhat like China’s version of the U.S. Export Administration Regulations (EAR), which is the primary legal tool used by the U.S. to restrict high-tech exports to China, such as semiconductors. These new regulations significantly expand and improve upon the “Export Control Law”, with various practical tools designed to strengthen enforcement. Unfortunately, the regulations were released over the weekend, and I imagine many Chinese lawyers and corporate compliance teams will have to sacrifice their weekend rest to study them.

During a Q&A session about the regulations, officials from the Ministry of Justice and MOFCOM stated that “the drafting of the regulations was “a decision made by the Communist Party Central Committee and the State Council”. They emphasized that the purpose of the regulations is not only to achieve effective control over dual-use items and safeguard national security and interests, but also to create a predictable trade environment and promote compliant trade in dual-use items. According to the officials, China’s export controls “align with international norms, are not prohibitive, and do not aim to hinder normal international exchanges, economic cooperation, or the smooth operation of global industrial and supply chains.”

The officials also revealed that MOFCOM is working on a unified export control list for dual-use items, which will be implemented in parallel with the regulations and will be dynamically adjusted based on technology development.

Given the technical nature of the regulations, I don’t intend to provide a full analysis, but I would like to highlight two clauses that I think are particularly important.

Article 49 : For certain goods, technologies, and services provided by foreign organizations and individuals outside China to specific countries, regions, organizations, or individuals for specific purposes, the Ministry of Commerce may require the relevant operators to comply with the relevant provisions of these regulations:

Dual-use items produced overseas that contain, integrate, or mix specific dual-use items originating from China.

Dual-use items produced overseas using specific technologies originating from China.

Specific dual-use items originating from China.

I would call this clause China’s version of the export control "de minimis rule" and the "foreign direct product rule (FDP)." As we know, these U.S.-developed extraterritorial export control rules are now used extensively to manage foreign-made items that contain a certain amount of U.S.-controlled elements or were produced using U.S.-controlled technology or equipment. In the past two years, these rules have effectively prevented companies like ASML in the Netherlands and Tokyo Electron in Japan from selling advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment to their Chinese customers as part of the extensive U.S. export controls against China.

Clearly, this inspired the Chinese government to design its own version of these rules.

However, unlike the U.S., the Chinese version of the "de minimis rule" and FDP rule merely stipulates that MOFCOM "may require (可以要求)" (rather than "shall require(应当要求)") the private sector to apply these rules and uses a rather vague term "refer to.(参照)"

The most authoritative interpretation of "refer to" comes from the “Legislative Technical Specifications” issued by China’s National People’s Congress, which states that it is generally used for "matters not directly covered by the legal scope but that are logically related." Though still very ambiguous, to me, this means that the related controls will exist in a space that is, to some extent, between law and policy. It gives the Chinese government legal authority, but also plenty of flexibility.

From a compliance perspective for domestic companies, its impact seems limited. However, from the perspective of using export controls as a countermeasure, this undoubtedly expands the application of China’s countermeasures outside Chinese territory in a nuanced way.

Given China’s importance in the global supply chain, this represents a significant shift for foreign companies closely cooperating with Chinese suppliers. For instance, if an EV battery produced in Mexico contains graphite mined in China, and since graphite is already subject to China’s export controls, this new rule could lead to the control of these batteries containing that graphite.

Similarly, given the importance of gallium and germanium in the next-generation semiconductors, will chips manufactured overseas using Chinese-produced gallium and germanium be subject to China’s export controls? Given China’s dominance in critical minerals, this clause essentially extends the deterrent effect of China’s critical minerals export controls beyond its borders—a highly strategic move.

This is a double-edged sword. Given the often arbitrary nature of Chinese policy-making, foreign companies may worry that using Chinese critical minerals, technology, and equipment in the future could subject them to Chinese export controls, potentially accelerating the "decoupling" of foreign supply chains from China.

The U.S. "de minimis rule" and FDP rule rely on its global technological dominance, whereas China’s version depends primarily on supply chain advantages in certain production stages. Technological advantages are hard to catch up with in the short term, but supply chain advantages can be reconstructed over time, especially if countries work together to create a non-China-dependent supply chain.

The Chinese government’s ambiguity on this rule likely reflects an awareness of this. To avoid unintended negative impacts, the Chinese government must carefully consider the timing, method, and scope of enforcement, while also providing clear rules and responding to potential international concerns.

Another clause worth noting is about international cooperation in export control, which is particularly relevant for China’s private sector in responding to U.S. export controls.